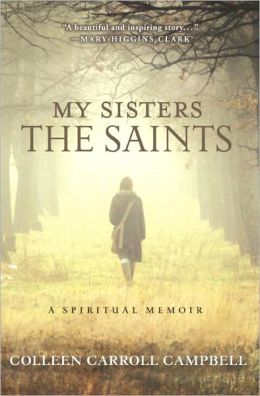

Book: My Sisters The Saints

Author: Colleen Carroll Campbell (no relation to reviewer)

Publisher: IMAGE

Have you ever grumbled to yourself, “Is this all there is? Why does my life feel so empty when I really ought to be grateful and happy?” You can list your achievements and count your blessings, but, still, a nagging sense of nothingness tugs on your sense of self, and you wonder why, why am I so miserable?

Colleen Carroll Campbell’s spiritual memoir, My Sisters the Saints, now on Virtual Book Tour, opens with the author’s own experience of “nagging discontent” and unfolds a remarkable 15 year, determined journey to find her female self, that “feminine part of me that I thought I had smothered with resumes and credentials.” (79). My Sisters the Saints offers a ground-breaking view of the challenges facing modern, educated women in discovering their female significance in a culture intentionally designed to measure women like men, by their sexual, material and professional achievements.

Here, we have an accessible, eloquent expression of New Feminism. Imagine a mix of Betty Freidan’s opportunity-seeking feminism and Caryll Houselander’s female-specific spirituality – utterly opposing views of the feminine and its significance in self-fulfillment. Campbell charts a very personal, moving struggle through this dichotomy in search of an authentic significance, the sort of peaceful, internal calm which signals a life on track. In so doing, she discovers that being female is more than biological accident.

Hers was not an easy journey. When Campbell suffered her first bout of malaise, she was already a perfect prototype, a product of the massive, concerted restructuring of female roles and expectations sparked by the 1963 publication of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Campbell’s life was molded and cast to subordinate marriage and family to the career objectives touted and taught by 20th century progressive feminism. A graduate of Marquette University, a member of the editorial board of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at age 24, and the only woman of six speech writers to President George W. Bush, Campbell fully embraced the goals and reaped the benefits of progressive feminism. Campbell admits that “feminism . . . was simply the air I breathed as a girl growing up in the 1970s and 1980s and coming of age in the 1990s.” (5). Like most young women today, she knew her priority: “I fiercely guarded my professional achievements as the core of my identity.” (82).

Campbell could not have known, could not have seen, that she came of age in a vast social experiment. Decades before Campbell was born, Friedan herself suffered a hunger for significance. Her emptiness motivated a series of surveys of other women. These women, mostly well-educated, white, suburban housewives like herself, expressed unhappiness in their lifestyle: “Is this all?” “I feel empty somehow . . . incomplete;” “I’m so dissatisfied.” Friedan diagnosed a “feminine mystique” as the cause of this “Problem That Has No Name,” a cultural prison which bound women to mindless domestic roles. She wrote:

These problems cannot be solved by medicine, or even by psychotherapy. We need a drastic reshaping of the cultural image of femininity . . . A massive attempt must be made by educators and parents – and minister, magazine editors, manipulators, guidance counselors – to stop the early-marriage movement, stop girls from growing up wanting to be “just a housewife,” stop it by insisting, with the same attention [given to] . . . boys, that girls develop the resources of self.” (TFM, 351).

This “drastic reshaping of the cultural image of femininity” proceeded apace, during the years that Colleen Carroll Campbell was born, went to school and came of age as a brilliant, well-educated young woman ready to take on the world in her restructured femininity – that new image of womanhood which sees child-bearing as a biological accident and marriage and domestic interest inferior to traditional masculine measures of achievement. Combined with the successful promotion of sexual permissiveness, birth control and abortion, progressive feminists have accomplished a massive indoctrination and “re-education” of females to a more “equal . . . image of femininity.” (TFM, 356). Campbell was exactly the type of new woman progressive feminists sought to manufacture: women who placed their autonomy and financial and career ambitions at the very core of their identity.

Now, on the 50th anniversary of The Feminine Mystique, Campbell – a child of the “drastic reshaping” of femininity – has published a new feminist treatise which, like The Feminine Mystique, evolved from Campbell’s own moment of utter disillusionment. In her opening chapter – Party Girl –Campbell writes of the feminist culture bequeathed her:

If the key to my fulfillment as a woman lies in maximizing my sexual allure, racking up professional accomplishments, and indulging my appetites while avoiding commitment, why has following that advice left me dissatisfied? Why do my friends and I spend so many hours fretting that we are not thin enough, not successful enough, simply not enough? If this is liberation, why am I so miserable? (5).

For Campbell, the progressive feminist experiment failed. True, she enjoyed its worldly opportunity and freedom to pursue “money, sex, power, and status.” But the “problem that has no name,” the sinking feeling of insignificance which Friedan insisted would be cured by paychecks and promotions, stirred unabated in Campbell’s “liberated” heart. She found herself adrift in an increasingly unfulfilling pursuit, without cultural icons or markers to deepen the experience of her life. Like Wendy Shalit, Carrie Lukas and other brave young women challenging the dishonesty of progressive feminism, Campbell refused to accept the malaise and sought models for “deep-down, joyful peace.”

Where are such models to be found? The thinning ranks of progressive feminists are disturbingly angry, like Friedan was, referring to themselves as “menopausal warriors” (N. Keenan) and their critics as “anti-feminists.” (S. Coontz). Increasingly, women of the Baby Boomer generation, my generation, women who themselves have discovered that they are not just the people “who happen to … give birth” and that their “equality and human dignity” are not just functions of earning a paycheck (TFM, 371) are speaking up, refusing to perpetuate the myths which mislead young women like Campbell into masculinized life styles. As Anne-Marie Slaughter dared to explain when leaving her high level State Department job to spend time with her family:

When I described the choice between my children and my job to Senator Jeanne Shaheen, she said exactly what I felt: “There’s really no choice.” She wasn’t referring to social expectations, but to a maternal imperative felt so deeply that the “choice” is reflexive.

But even with such public admissions, we are a long way from offering detailed guidance to young women for fashioning a workable balance between work and family, much less how to secure a sense of feminine self that feels authentic and significant.

Where can young women turn for understanding and guidance on their inner most longings as women? Campbell turns to a source that has offered a rich tapestry of the “maternal imperative” over the ages. Whether raised Catholic, as Campbell was, or not, the treasury of the Catholic Church teems with stories of women who found, captured and deployed the “desires that [spring] from a soft, passionate, feminine part” of a woman’s being. (79). Caryll Houselander once described this vast store of experience and wisdom as “a grandmother . . . with a fortune, indeed, and we dare not miss it; but she certainly has a lot funny old hats and shawls and beliefs and traditions, none of which seem to be fashionable or useful or even wearable.” (RoG, 92). It’s a fortune, nonetheless, that represents two thousand years of compiled information by and about women – a fortune amazingly disowned by Friedan feminists as patriarchal, even as they crafted strategies to capture the spoils of the patriarchy they decried.

Campbell’s chronicle reminds me of my own gratitude to the women I searched out and found as spiritual guides as I wrestled years ago with my conflict between career and family goals. Like Campbell, I seemed curiously to cross paths with women just when I most needed them, as I was frantically looking for the next stone in raging waters. The writings of Erma Bombeck and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, for example, lifted me and stretched my thinking and spiritual life in directions I could not have found without them.

Perhaps unintentionally, in sharing this personal, beautifully written journey, Campbell now contributes herself – her pain, her challenges, her spiritual growth and her faith – to the feminist treasury, a stunningly rich treasury open to all young women wondering why, as Campbell did, with academic credentials, paychecks and careers, “why am I so miserable?”

Campbell’s feminist discoveries are worth reading repeatedly and sharing broadly.