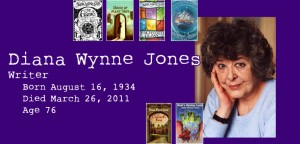

Diana Wynne Jones died on March 26, 2011. I had only come to know of her work in 2004 when Hayao Miyazaki turned her novel Howl’s Moving Castle, into an animated film. After seeing the film, I decided to find out what I could about the author, and in the process, I discovered one of the greatest writers of the 20th century.

Jones’ book, Reflections on the Magic of Writing, gives some interesting insight into the ideas which lay behind her work. While she was regarded as a “children’s author,” she was really writing books to be read and enjoyed by anyone, like C. S. Lewis did before her, and J.K. Rowling and so many have done after. While there can be, and should be, much which is said about her fiction, what I found interesting is that the challenges she faced as an author reflected the kinds of challenges she faced as a woman. As both an author and woman, she grappled with expectations which she felt pressured to meet and follow, whether or not those expectations made any sense. That she wrote “children’s fantasy” was often seen as something unsuitable for a woman – just as she had discovered in her youth that being the hero of a fantasy was largely reserved for boys.

In essays like “The Heroic Ideal: A Personal Odyssey” and in lectures from her “Whirlwind Tour of Australia,” Jones expressed the difficulty she had creating a feminine heroine for her stories. She was afraid that such heroines would not be universal – girls might like such stories, but would boys? She loved classical myths and legends and grasped at any feminine hero she could find – Spenser’s Britomart, for example, and the Ballad of Tam Lin. slowly, in her works, she introduced strong feminine characters, sometimes wiser or more powerful than the masculine “hero.”

But Jones, like society generally, had to come to accept the possibility of a feminine hero in a story which could be enjoyed by everyone. She saw it could be done – others were creating and presenting feminine heroes to the broader audience. In her own efforts, Jones realized that there was an aspect of herself she had to confront, the reality of being a woman and being comfortable in her own skin. Creating a story of a feminine hero was as helpful to Jones’ personal growth as it was to children’s literature:

“About ten years ago, boys started being prepared to read books with a female hero. I found everything had gone much easier without, then, being able to say how or why. Females weren’t expected to behave like wimps and you could make them the center of the story. By that time anyway, I found the tactile sense of being female stopped bothering me – which may have been a part of the same revolution – and it was a release.” (Jones, Reflections on the Magic of Writing, 147).

The book which Jones she wrote – Fire and Hemlock – was a complex work which allowed Jones to borrow many heroic themes and turn them upside-down and inside-out. The hero of the tale reflects themes found in works as diverse as The Odyssey and Sleeping Beauty. It is a tragic tale about love and the real expectations of love. There are aspects of the relationship which might seem creepy to the reader, but they are resolved before the end (I say this as a warning as well as to point out Jones dealt with those problems, but to say more would ruin the story).

Sadly, the story ran afoul of the expectations of critics and many dismissed it. One critic went so far to imply that he wouldn’t read it since it was clearly written for women!

In her writing, Jones’ often reflects on “rules” – and how arbitrary or ridiculous they can be. As a child during World War II, Jones grew up in a rule-bound household. The difficult relationship she had with her parents and the rules they imposed upon her became the foundation of her criticism of “rules” and her desire to break through rule compliance to find something greater, better as a result. Jones is not an anarchist: in her writing and in her life, she believed principles are the primary markers for behavior, while social constructs suffer defects and limitations. Jones acknowledged that rules can represent some element of truth, but one must not confuse them for the fullness of truth itself.

The best way to understand Jones’ interest in rules-as-subject is through her great work of literary criticism: A Tough Guide to Fantasyland. In this work, Jones organized all the cliché in the fantasy genre and whittled it down into a “guidebook” to reflect the tone and style of “fantasy novels.” She concluded that people were writing the same story over and over again – borrowing, ultimately, from Tolkien. Tolkien himself was not caught in the cliché and transcended the imitators; his purpose was never to establish the “rules” of fantasy writing. But Tolkien’s writing worked so well, it generated “rules” which allowed other writers to imitate him. Jones sees the value to the rules, but laments how much is lost when the freedom of imagination that fantasy invites becomes so restricted.

Jones’ analysis of the “rules” of fantasy writing offers a broader framework to understand how rules of behavior and expectation can generate from a model of excellence into a restrictive and confining set of rules that forestalls development and further excellence. New Feminists, for example, might look at 20th century feminism and fairly wonder how does one conserve what deserves to be conserved while moving forward? Have the “rules” of 20th century feminism taken over the lives and expectations of women, thwarting the further “excellent” developments New Feminism might offer?