In the early Church, many virgin women were killed by Rome. While these women infuriated authorities for proclaiming their faith in Christ, it seems that something else put them in the spotlight for persecution: they denied Rome’s social mores by exerting bodily self-determination.

Even though the ancient world had some powerful women with a great deal of freedom, for most women, such freedom was but a dream. Generally, women were raised under the authority of their father and then married to find themselves under the authority of a husband. Most women’s lives were controlled and dictated by this male authority exerted legally over “their” women like any other item of property.

Christianity, with its promotion of continence and virginity, suggested new paths for women, ones in which they did not have to end up under the direct authority of a man. Christianity introduced options by which women could take possession of their own lives, their own destiny – and, importantly, be respected for it.

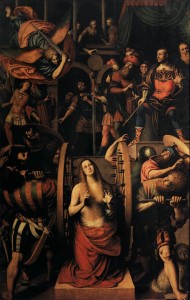

In this way virgin martyrs like St Catherine of Alexandria declared that they and they alone controlled their own bodies. They exerted themselves as persons possessed of the same dignity as men. These women positioned themselves socially as moral actors, free to make decisions over their own body. They rejected the prevailing social norm of male authority and control over them.

To be sure, ancient society believed the government possessed authority over people and could make demands of them, including demands upon the use of the physical body. So control over one’s body, even for the average man, was relative.

It was this limited status – the same as men but much more restricted than today- which women claimed for themselves. They did so under the direction of the greater moral authority given to them by God through their creation and moral conscience. This revolution – a literal revolt against government authority – did not just benefit women. Men, too, would come to draw upon this revolution in thought to free themselves from false obligations to the state and to assert a greater level of self-determination, following a higher authority to become authentic, moral persons in the world.

This authority over one’s own body was seen as a kind of stewardship, because God was the one who had ultimate control. With God in control, no human could claim absolute authority over another. This granted true freedom, because God, the greatest authority, had given it. Self-determination was guaranteed. Moral demands were placed upon what one could or could not do, with a range of consequences imposed when one failed to meet the basic moral law, to be sure – but the person was still guaranteed control over one’s body. This was not merely a libertine right: it was also a responsibility (which is lost in the libertine arguments we hear today).

In this way the Christian tradition helped establish the belief that people should be in control of their own bodies. The virgin-martyrs represented this ideal in its fullness: they kept complete control of their bodies, of their own destiny, and nothing – not even the brutalities fostered upon – could take that power from them.

We only hear half of this truth today. When people speak about having control over their own bodies, the rhetoric is used to justify all kinds of abandonment of bodily control. We are told one can and should do whatever they want with their body, implying that if one’s body desires something, that craving should be heeded. But this means such a person is no longer in control of their body: the body controls them. Caving in to the impulses, the consequences can be dire. “Safe sex” is hardly safe, as statistics easily show. It is artificial and represents an attempt to hide from the self one’s own actions, to prevent oneself from owning one’s own actions.

Today, control of one’s own body is often brought up in the debate over abortion. But we can see that those asserting control over the body to defend abortion end up contradicting themselves: abortion affects the life of another, destroying the body of another. This returns us to a hierarchical view of bodily control, where some bodies are seen as the possession of others. The acceptance of abortion rejects the rights of a person to control their own bodies. It is the ultimate inversion of all such rights because it permits and supports the denial of bodily rights, taking bodily control away from one self and making that self the possession of someone else.

People have a right to control their own bodies. But that right is, as with every right, a responsibility. When the responsibility is neglected and turned aside, when the right it seen as a freedom to act without consequences, the only thing which can happen is the overturning of the right itself.

And this is exactly the problem which faces us today.

Thanks for your work on this article. I think I disagree with your emphasis here, but then perhaps I’m misunderstanding something. It isn’t clear to me that the advent of Christianity brought a significant increase in the ability to self-govern the body, or that Christianity considers this of great importance, so much as the exhortation to self-govern the heart, will, intellect, and other aspects of the interior life. More significant as I see it is Christianity’s recognition that we should be free to do good no matter what state of freedom or constriction we find our bodies in. Christianity’s main message was that this freedom is possible whether, as pertaining to our bodies, we be slave or free, male or female.

The outward, bodily freedom is a natural result of a society that largely accepts the idea of self-governance in interior matters, but the outward, bodily freedom is not something to strive for in and of itself. Many who are bodily free and self-governing are poor in virtue, while many who are all but bodily enslaved are masters of interior virtue; in fact, we often see a correlation such that those with less physical freedom seem to tend more toward the interior freedom that Christianity esteems. Is it perhaps for this reason, among others, that Our Lord teaches us not to be fearful of those with control over our bodies, but rather fearful of those who can destroy our souls (Mt. 10:28)?

Well, there are many issues which come together in one. As I tried to point out, Christianity promoted moral values which were expected of one for one’s body, but those responsibilities then led to an increase in an understanding that one did control one’s own body. The early virgin martyrs and many of the virgins and widows who were promoted by the early Church found this aspect of the Christian faith new and gave them a great sense of freedom — they really did get to think beyond the social mores and establish a new kind of society. Some, like St. Ambrose, really took this much further and really had a great vision of a new society, and this included new understanding of the body. Yes, there were all kinds of intrinsic issues, but the bodily notion and interests proves itself quite strongly in connection to sexual ethics which emerged. They only made sense in connection with greater sense of personal responsibility and freedom.

A good work (though not without its faults) is Peter Brown’s work, The Body and Society. Of course it goes further into issues which I did not address here, but you can see the reformation of society which came about from Christian notions of the body in this work.

Later, in the Middle Ages, this drive would once again be found with women saints and mystics, though with new, medieval ideas added to notions of bodily control, so new images and ways of expressing control of one’s body was found (Bynum’s work, Holy Feast and Holy Fast for example does this with notions of food, and how women saw the body in relation to food in the midst of great famines and the like).