Bringing back the concept of the woman as sacred requires that we, women, act like she is. Because if we act like it then men will too. And lingerie companies will. And the music industry will.

The problem is many of us don’t really feel like we are sacred. We may not even believe that we are. But feelings can always be overcome. And when a fact is true, sometimes we need to merely act as if we believe it, and then the belief (and the feelings,) will follow.

Let’s start with the outside. Wear what you would wear if you truly believed you held something sacred.

Wear makeup it if you think it adorns you well, but don’t wear it as a mask to hide behind. Don’t be as concerned with the trend, or the label, or how perfectly straight you can get your hair to go. I was amazed going from a high school with uniforms to college how the majority of college girls all dress the same. And I don’t think anyone would claim it to be a very pretty outfit (nike shorts, t-shirt, leggings, tennis shoes.) And yet don’t we want to be the girl who is completely “herself”—who dresses in her own style and doesn’t need to blend? We want to be comfortable like her. We are just scared that we aren’t beautiful enough. We don’t believe we are sacred. So choose to believe it. Ask yourself what you would wear if you truly believed you were beautiful.

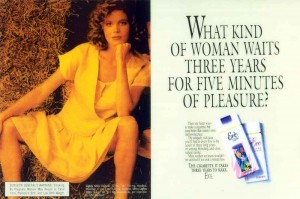

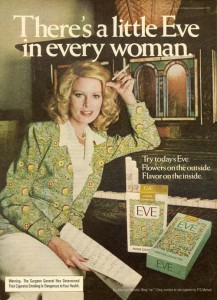

And then think about too, how much you would reveal, if you truly believed you were sacred. It is true that in an ideal world covering up would not be necessary, considering how beautiful and sacred the female body is. But our culture has damaged the bond between sacred and sexual, and baring all can detract attention away from the sacred. We know this, and that is why we all have a line somewhere with regard to modesty. But think about modesty in terms of what you would wear if you did not fear disapproval or rejection. What would you wear if you knew you were beautiful and did not need to draw attention to your sexuality? Sometimes we feel entitled to show off, and when we are chastised our interior response may be you’re just jealous. Besides, if nobody else covers up, who will pay us attention if we do?

But here again, we must choose to commit to the fight. And wait patiently on the men to follow. Because they will.

For deep inside every man is a jaded little boy who wished he could be a knight and wants that princess who he can protect and adorn. But we have taught him that that princess does not exist. That instead, he can have quick pleasure and excitement from the toys we make of ourselves. But if we want men to get away from the TV screen on the night of the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show, we have to stop watching. We must exit the race. For it is a futile one. The sexy, the shocking, even the cute—it all ends. It all fades. The only thing that remains is the sacred. And we must embrace it and protect it and demand that it be respected by others.

I want to finish with the fairy tale of Cinderella. Cinderella teaches us the most important lesson about beauty. She did not have the luxury of buying beautiful dresses (up until the Fairy Godmother arrival.) She wore rags and she spent her days cleaning and scrubbing and well, being alone. If anyone could have determined that no one found her beautiful or wanted her it would be Cinderella. But Cinderella is the fairy tale princess. Why? Because she was by far the most beautiful. She did not let anything destroy her goodness, her virtue, her must precious self. She loved as if others loved her. She wore her rags as if they were a ball-gown. She sang as if people listened. She knew that she was a princess and so she did not let anything embitter her or make her think otherwise. She made her whole self beautiful by primarily making her heart beautiful. And as we know, if the heart is beautiful, well, a bodily imperfection becomes laughably insignificant.

But then there is always the objection:

What if my Fairy Godmother never sends me the prince.

This is a loneliness that many women have to deal with and it is the reason fairy tales are blamed with giving little girls false hope. But the unspoken truth of Cinderella is that she would have remained a princess even if she had never gone to the ball. Cinderella was happy even in the midst of her loneliness. Even while no one seemed to notice her beauty. And that is the wonderful thing about womanhood. Like a lonely temple in a desert, it does not lose its beauty just because no one is admiring it. The beautiful woman is a happy woman because she is living her life like she should. And the sacred within her is the most important part of her. She nurtures it, she adorns it, and she shares it. The beautiful woman loves. And when a woman loves, her angel wings take her higher than any plastic Victoria’s Secret imitation ever could.